Hudson Bay

| Hudson Bay | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Location | Arctic Ocean |

| Countries | Canada |

| Max. length | 1,370 km (851.28 mi) |

| Max. width | 1,050 km (652.44 mi) |

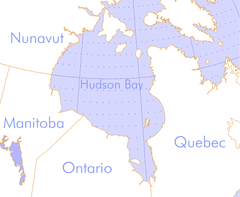

Hudson Bay (French: baie d'Hudson) is a large body of water in northeastern Canada. It drains a very large area that includes parts of Ontario, Quebec, Saskatchewan, Alberta, most of Manitoba, southeastern Nunavut, as well as parts of North Dakota, South Dakota, Minnesota, and Montana. A smaller offshoot of the bay, James Bay, lies to the south.

The Eastern Cree name for Hudson and James Bay is Wînipekw (Southern dialect) or Wînipâkw (Northern dialect), meaning muddy or brackish water. Lake Winnipeg is similarly named by the local Cree, as is the location for the City of Winnipeg.

Contents |

Description

Hudson Bay is 1,230,000 square kilometres (470,000 sq mi), making it the second-largest bay in the world (after the Bay of Bengal). It is relatively shallow, with an average depth of about 100 metres (330 ft) (compared to 2,600 meters in the Bay of Bengal). It is approximately 1,370 km (850 mi) long and 1,050 km (650 mi) wide.[1] On the east it is connected with the Atlantic Ocean by Hudson Strait, and on the north with the rest of the Arctic Ocean by Foxe Basin (which is not considered part of the bay) and Fury and Hecla Strait. Geographic coordinates: 78° to 95° W, 51° to 70° N.

History

English explorers and colonists named Hudson Bay after Henry Hudson, who explored the bay in 1610 on his ship the Discovery. On his fourth voyage to North America, Hudson, worked his way around the west coast of Greenland and into the bay, mapping much of its eastern coast. The Discovery became trapped in the ice over the winter, and the crew survived onshore at the southern tip of James Bay. When the ice cleared in the spring Hudson wanted to explore the rest of the area, but the crew mutinied on June 22, 1611. They left Hudson and others adrift in a small boat. No one knows the fate of Hudson and the crewmembers stranded with him, but historians believe they died.

Sixty years later the Nonsuch reached the bay and successfully traded for beaver pelts with the Cree, leading to the creation of the Hudson's Bay Company (HBC), which still bears the historic name. The HBC negotiated a trading monopoly from the British crown for the Hudson Bay watershed, called Rupert's Land. France contested this grant by sending several military expeditions to the region, but abandoned its claim in the Treaty of Utrecht (April, 1713).

During this period, the Hudson's Bay Company built several forts and trading posts along the coast at the mouth of the major rivers (such as Fort Severn, Ontario, York Factory, Manitoba, and Churchill, Manitoba). The strategic locations were bases for inland exploration. More importantly, they were used as trading posts with the indigenous peoples who came to the posts with furs from their trapping season. The HBC shipped the furs on to Europe and continued to use these posts until the beginning of the 20th century. The port of Churchill is still today an important shipping link for trade with Europe and Russia.

In 1870, when HBC's trade monopoly was abolished, it ceded Rupert's Land – an area of approximately 3.9 million km² – to Canada as part of the Northwest Territories. Starting in 1913, the Bay was extensively charted by the Canadian Government's CSS Acadia to develop it for navigation. This mapping progress resulted in the establishment of Churchill, Manitoba, as a deep-sea port for wheat exports in 1929, after unsuccessful attempts at Port Nelson.

Due to a change in naming conventions, Hudson's Bay is now called Hudson Bay. As a result, the names of the body of water and the company are often mistaken for one another.

Geography

Extent

The International Hydrographic Organization defines the northern limit of Hudson Bay as follows:[2]

A line from Nuvuk Point () to Leyson Point, the Southeastern extreme of Southampton Island, through the Southern and Western shores of Southampton Island to its Northern extremity, thence a line to Beach Point () on the Mainland.

Climate

Hudson Bay was the growth centre for the main ice sheet that covered northern North America during the last Ice Age. The whole region has very low year round average temperatures. (The average annual temperature for Churchill at 59°N is -5°C; by comparison Arkhangelsk at 64°N in a similar cold continental position in northern Russia has an average of 2°C.[3]) Water temperature peaks at 8°-9°C on the western side of the bay in late summer. It is largely frozen over from mid-December to mid-June when it usually clears from its eastern end westwards and southwards. A steady increase in regional temperatures over the last 100 years has been reflected in a lengthening of the ice-free period which was as short as four months in the late 17th century.[4]

Waters

Hudson Bay has a salinity that is lower than the world ocean on average. This is caused mainly by the low rate of evaporation (the bay is ice-covered for much of the year), the large volume of terrestrial runoff entering the bay (about 700 km³ annually; the Hudson Bay watershed covers much of Canada, with many rivers and streams discharging into the bay), and the limited connection with the larger Atlantic Ocean (and its higher salinity). The annual freeze-up and thaw of sea ice significantly alters the salinity of the surface layer, representing roughly three years' worth of river inflow.

Shores

The western shores of the bay are a lowland known as the "Hudson Bay Lowlands" which covers 324,000 km². The area is drained by a large number of rivers and has formed a characteristic vegetation known as muskeg. Much of the landform has been shaped by the actions of glaciers and the shrinkage of the bay over long periods of time. Signs of numerous former beachfronts can be seen far inland from the current shore. A large portion of the lowlands in the province of Ontario is part of the Polar Bear Provincial Park, and a similar portion of the lowlands in Manitoba is contained in Wapusk National Park, the latter location being a significant Polar Bear maternity denning area.[5]

In contrast, most of the eastern shores (the Quebec portion) form the western edge of the Canadian Shield in Quebec. The area is rocky and hilly. Its vegetation is typically boreal forest, and to the north, tundra.

Measured by shoreline, Hudson Bay is the largest bay in the world (the largest in area being the Bay of Bengal).

Islands

There are many islands in Hudson Bay, mostly near the eastern coast. All are part of the territory Nunavut. One group of islands is the Belcher Islands. Another group includes the Ottawa Islands.

Geology

When Earth's gravitational field was mapped starting in the 1960s a large region of below-average gravity was detected in the Hudson Bay region. This was initially thought to be a result of the crust still being depressed from the weight of the Laurentide ice sheet during the most recent Ice Age, but more detailed observations taken by the GRACE satellite suggest that this effect cannot account for the entirety of the gravitational anomaly. It is thought that convection in the underlying mantle may be contributing.[6]

Some geologists disagree about what created the semicircular feature, known as the Nastapoka Arc, of the bay. The overwhelming consensus is that it is an arcuate boundary of tectonic origin between the Belcher Fold Belt and undeformed basement of the Superior Craton created during the Trans-Hudson orogen. Although, a few geologists have argued that it is possibly related to a Precambrian extraterrestrial impact and have compared it to Mare Crisium on the Moon, a complete lack of credible evidence for such an impact crater has been found by regional magnetic, Bouguer gravity, and geologic studies.[7]

Coastal communities

The coast of Hudson Bay is extremely sparsely populated; there are only about a dozen villages. Some of these were founded in the 17th and 18th centuries by the Hudson's Bay Company as trading posts, making them part of the oldest settlements in Canada. With the closure of the HBC posts and stores in the second half of the 20th century, many coastal villages are now almost exclusively populated by Cree and Inuit people.

Some of the more prominent communities along the Hudson Bay coast are:

- Puvirnituq, Quebec

- Arviat, Nunavut

- Churchill, Manitoba

- Rankin Inlet, Nunavut

Military development

Not until the Cold War was there any military significance attributed to the region. In the 1950s, a few sites along the coast became part of the Mid-Canada Line, watching for a potential Soviet bomber attack over the North Pole. The only Arctic, deep water port in Canada is located at Churchill, Manitoba.

Economy

Arctic Bridge

The longer periods of ice-free navigation and the reduction of Arctic Ocean ice coverage have led to interest in Russia and Canada in the potential for commercial trade routes across the Arctic and into Hudson Bay. The so-called "Arctic Bridge" would link Churchill, Manitoba and the Russian port of Murmansk.[8]

See also

- List of Hudson Bay rivers

- Great Recycling and Northern Development Canal

- Hudson's Bay Company Archives

- Tyrrell Sea

References

- ↑ http://www.infoplease.com/ce6/world/A0824440.html

- ↑ "Limits of Oceans and Seas, 3rd edition". International Hydrographic Organization. 1953. http://www.iho-ohi.net/iho_pubs/standard/S-23/S23_1953.pdf. Retrieved 6 February 2010.

- ↑ GHCN climatic monthly data, GISS, using 1995–2007 annual averages

- ↑ General Survey of World Climatology, Landsberg ed., (1984), Elsevier.

- ↑ C. Michael Hogan (2008) Polar Bear: Ursus maritimus, globalTwitcher.com, ed. Nicklas Stromberg

- ↑ Young, Kelly (10 May 2007). "Satellites solve mystery of low gravity over Canada". New Scientist. http://space.newscientist.com/article/dn11826-satellites-solve-mystery-of-low-gravity-over-canada.html. Retrieved 2007-05-11.

- ↑ Eaton D. W. and F. Darbyshire, 2010, Lithospheric architecture and tectonic evolution of the Hudson Bay region. Tectonophysics. v. 480, pp. 1–22.

- ↑ [1] The Globe and Mail, Toronto, 18 October 2007, Russian ship crosses 'Arctic bridge' to Manitoba

- Atlas of Canada, online version.

- Some references of geological/impact structure interest include:

- Rondot, Jehan (1994). Recognition of eroded astroblemes. Earth-Science Reviews 35, 4, p. 331-365.

- Wilson, J. Tuzo (1968) Comparison of the Hudson Bay arc with some other features. In: Science, History and Hudson Bay, v. 2. Beals, C. S. (editor), p. 1015–1033.

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||